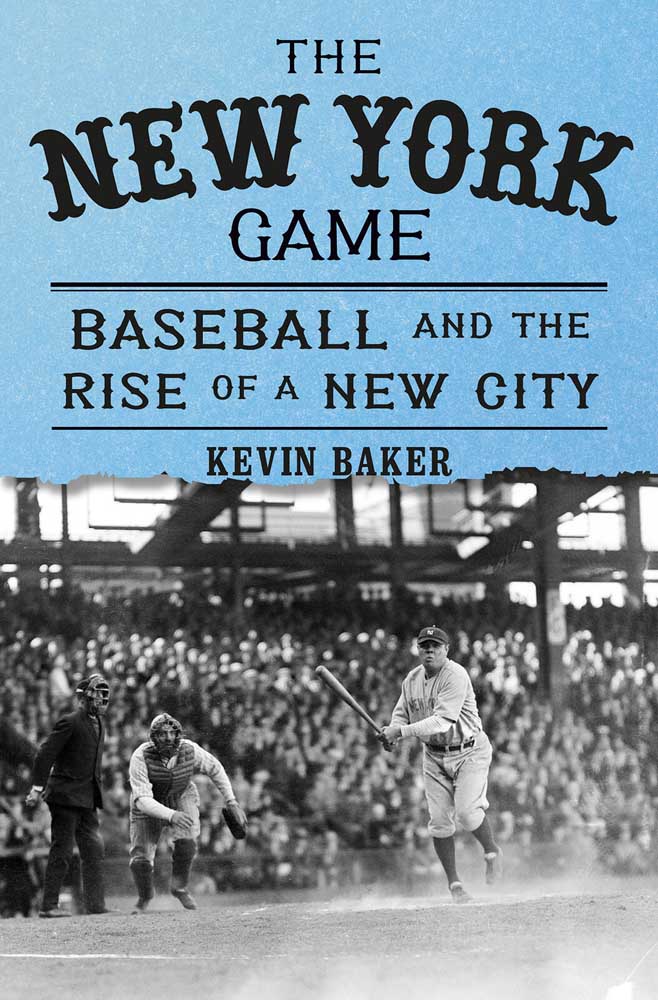

New book shows how much New York and baseball need each other

Published 3:00 am Tuesday, March 26, 2024

- BOOKS-BOOK-NEWYORK-BASEBALL-MCT

No one took advantage of being famous like Babe Ruth. Arguably the most recognizable athlete in American history roamed Manhattan in the early part of the 20th century satisfying his massive appetites.

Trending

The symbiotic relationship that Ruth created with his adopted home would be replicated time and again. Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio, Reggie Jackson, Derek Jeter all would thrive there — and that relationship extended well beyond individual players or even teams. It was about the most American of cities and the most American of sports.

In “The New York Game: Baseball and the Rise of a New City,” Kevin Baker makes the case that America’s financial, media and cultural capital and its national pastime grew not in parallel, but were inextricably intertwined.

Baker, a novelist, journalist and historian who co-authored Reggie Jackson’s “Becoming Mr. October,” walks us into the early 1900s as New York comes of age. Skyscrapers begin to blossom (just two years into the new century, there are 66 in Lower Manhattan), along with landmark developments such as Columbia University, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Trending

The game, still in its infancy (the first professional team was formed in the late 1860s), was perfectly suited to entertain its seething masses.

Doctors, lawyers, accountants, shopkeepers and secretaries had disposable income and leisure hours, and they needed somewhere to spend them both, either by watching in person or, eventually, listening to the play-by-play.

Baseball fit the bill, played across nine innings and a long season where teams or individual players could go through winning streaks or slumps. Drama came in the form of single contests, as well as rivalries stretched across months, hurtling toward an eventual championship.

The sport was “episodic and discrete, with every contest adding to the ongoing narrative of the pennant race,” Baker writes.

This would become especially evident in the 20th century, when baseball formed another critical partnership with the radio.

Millions in New York followed the travails of seasons with the likes of Red Barber, the legendary voice of first the Brooklyn Dodgers and then the New York Yankees. His ability to connect with his listeners and expand the audience beyond those in the stadium foretold the billions that would ultimately be spent for sports media rights in baseball and beyond.

We learn about the micro-economies that build up around the ballparks and the roots of well-known rituals, including what was likely the nation’s first sports bar. Back in 1890, the Home Plate Saloon was where the athletes mingled with the stars of the day.

Baker makes the case that some of the best baseball at the turn of the century was played in all-Black New York games whose scores were never reported in a newspaper. Repeatedly rejected by all-White teams, Black players’ attempt to create a literal league of their own failed in 1886, forcing them into traveling teams without permanent fields to play on. The Negro National League would form in 1920, with other regional leagues following. But it was a New York team, the Dodgers, with whom Jackie Robinson finally broke the color barrier in pro baseball. His start in 1947 was the first by a Black player in the majors since 1884.

The New York Game wraps up with World War II overshadowing just about everything. Baseball is a salve and a distraction, especially DiMaggio’s gripping 56-game hitting streak in 1941, just before the U.S. entered the conflict.