Timeless Lessons From Hawaii’s Oldest Settlement

Published 5:35 am Wednesday, February 19, 2025

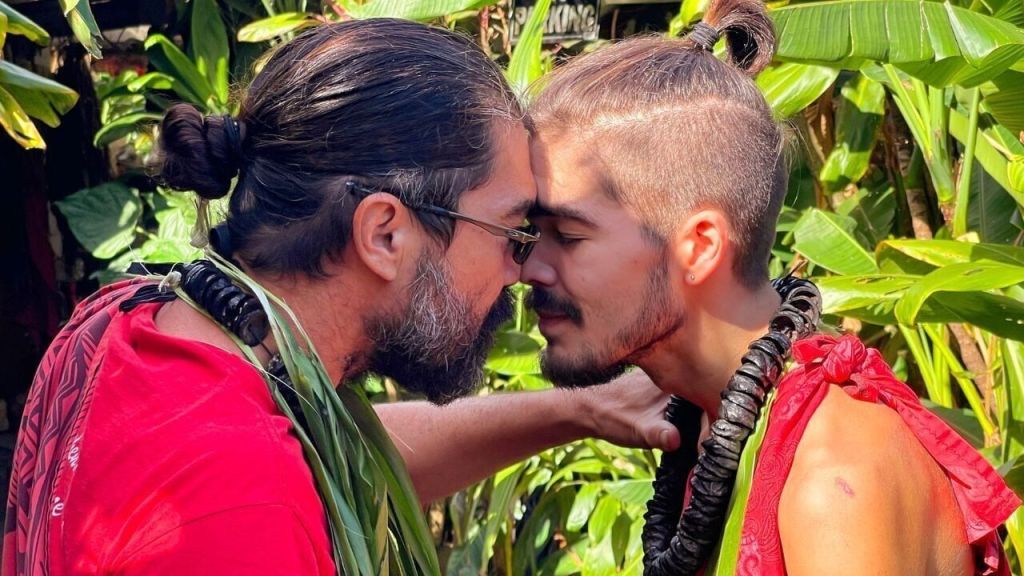

- Image Credit: Dai Mar Tamarack.

President Trump’s inaugural speech promised, “We will forge a society that is colorblind and merit-based.” What followed was the rapid disappearance of diversity and ethnicity-based programs, leaving Native Hawaiian leaders fearful for the fate of their communities.

Trending

Coleman Concierge recently visited the last remaining original family living in Hawaii’s oldest inhabited valley. They shared a different perspective — one of inclusion rather than omission. Journey with us to hear their timeless lessons on how celebrating diversity and traditions teaches us that we are more similar than different.

Braving the Pailolo Crossing

Our vessel, Safari Explorer, rocked and swayed as we crossed the Pailolo Channel to Molokai. The crew confined us to our quarters for safety. We were on our way to take a cultural tour of Halawa Valley, the oldest continually inhabited area in Hawaii, dating back to 650 CE.

While in our cabin, we tuned into Sons of Halawa, which played on a loop on the TV. This award-winning film tells the story of Pilipo Solatorio, the last of his generation living in the isolated valley, and his quest to find a successor. Spoiler alert: Pilipo’s son, Greg, was chosen to carry Halawa’s cultural treasures.

The film immersed us in the traditions of Halawa, but it was released in 2015. We couldn’t help but wonder what had changed in the decade since.

Our First Glimpse of Halawa

As we traveled in vans from our UnCruise ship docked in the harbor toward the far end of the island, we caught our first glimpse from the Halawa Valley Overlook. We saw two waterfalls, one dropping 250 feet, the other 500 feet into a densely forested gulch. The valley widened past the falls as it extended two miles to a small bay. We had already passed the last electric pole a few miles back and lost cell reception as we descended.

Greg’s son, Devak, met our tour group at a small park near the end of the road. A slight young man in his late teens or early 20s, he wore a brilliant red traditional rectangular shawl called a kihei.

After a brief introduction, he led us toward his family home, pausing several times to sound his conch shell, a traditional way to ask permission to enter. As we got closer, we heard a conch answer in affirmation. Naturally, someone joked about ancient Hawaiians using “shell phones” to call their friends.

Exchanging Ha

Greg met us on the outskirts of his home, where we conducted a gift offering ceremony before exchanging ha, the breath of life. The ceremony involves pressing together the bridge of the nose and the forehead while inhaling simultaneously. It was a profound experience — more intimate than a handshake but without the connotations of a kiss. For Greg, it was a prerequisite level of intimacy and respect before entering the home his family has occupied for generations.

Greg didn’t lecture us about ha‘s presence in “aloha.” That wasn’t his teaching style. Instead, he followed a traditional approach: watch, listen, be quiet, learn, work.

He explained: “What I’ve learned from my elders is that culture is sacred, not secret. You learn culture from the inside out, not the outside in. You learn culture from seeing, touching, holding, feeling, tasting. If I can share that with my visitors, and if they can see that with me, and if I can see that with them, we find out where our cultures connect.”

Traditional Hawaiian Learning

For the rest of the afternoon, Greg shared his culture in the traditional way. He showed us photographs from his father’s childhood when Halawa Valley was an active farming community with thousands of inhabitants. Instead of a dense forest, there were terraced fields, a poi factory, a school, a church, and a swinging bridge across the creek.

We listened as he recounted the 1946 tsunami, a story he had heard growing up. A warning had arrived 10 hours earlier, but no one understood the word “tsunami.” The community came together for self-rescue and rebuilding.

He continued by pulling out a wooden pounding board that had been in his family for eight generations, called a papakuiai, and preparing kalo (poi) in the traditional way. We watched as he smashed the steamed roots into a substance resembling mashed potatoes, which gradually transformed into a smooth, elastic dough. We held the finished product in our hands and tasted it. Its subtle flavor brought me closer to Hawaiian culture than the taro donut I had purchased from the ABC Store back in Kona, dyed purple and smothered in powdered sugar.

Reflection on Ohana

I walked along the beach near the end of my time in Halawa and passed by Pilipo’s memorial, still adorned with fresh flowers and mementos. I remembered something Greg had said: “In Hawaiian culture, everything revolves around the family. Ohana, ohana, ohana, ohana, ohana. That’s one thing Walt Disney got right: ohana.”

Pilipo was gone, and my visit to Halawa looked much different than the documentary, which was filled with family gatherings and storytelling. I saw Greg and Devak living off the grid in a traditional lifestyle, without the extended family, keiki (children), or kūpuna (elders). I wondered about Greg’s wife and other children.

The Sons of Halawa overview ends with, “Only through true commitment and sacrifice will Halawa’s story and sacredness be kept alive.”

I exchanged contact information with Greg before leaving to learn more about what it means to be the chosen son. We resumed our conversation over Google Meets while he was with his wife, Jenn, in Oahu.

Continuing the Conversation

From Greg’s perspective, succession was never in question. “Ever since I was a little kid, this is all I wanted. I’ve never wanted anything else. I’ve always wanted to be like my dad.”

Jenn knew Greg would return to Halawa when they met. She moved to Los Angeles for a while but saw Greg’s vitality fade the longer he was away from the islands. She felt herself slipping away on the mainland, too, but her home was Oahu. When they were living together there, it was never a question of whether Greg would move back, only when. Their vacations weren’t to Disneyland — they took the kids home to Halawa.

Lines of Succession

In 2012, as his parents aged, Greg knew it was time. He moved to Halawa and took breaks to visit Jenn in Oahu. They see each other for a few days each month, but the rest of the time, Greg lives off the grid, providing his own food and fixing anything that breaks. He lost his mother in 2021, but Devak joined him before he lost his father in 2023.

The Future of Halawa

Today, Greg and Devak continue the family legacy of traditional living and conducting cultural tours. Greg acknowledges the challenges but wouldn’t have it any other way. As for the future, he says:

“I’m still practicing the traditions and the culture, sharing like he (Pilipo) did, working on the place just like he did. It’s just a matter of who will be the successor that will carry on the cultures and traditions of the valley. Hopefully, it will be my older son (Devak), but like my dad says, it’s all up to the people you’re teaching. There’s no real certain future. All we can do is teach.”

After our conversation, I realized my thoughts on sacrifice weren’t complete. Perhaps my judgment was clouded by the endless possibilities of mainland life instead of focusing on the essentials. Greg says Halawa comes from two words: ha, the breath of life, and lawa, meaning sufficient. Halawa means “sufficient life.” What more could one ask for than family, purpose, and cultural identity?